Mental Health Therapies - Insight therapy

Insight therapy is the umbrella term used to describe a group of different therapy techniques that have some similar characteristics in theory and thought. Insight therapy assumes that a person's behavior, thoughts, and emotions become disordered because the individual does not understand what motivates him, especially when a conflict develops between the person's needs and his drives. The theory of insight therapy, therefore, is that a greater awareness of motivation will result in an increase in control and an improvement in thought, emotion, and behavior. The goal of this therapy is to help an individual discover the reasons and motivation for his behavior, feelings, and thinking. The different types of insight therapies are described below.

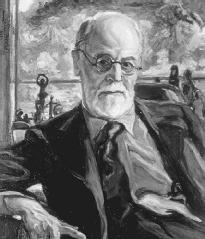

Psychoanalysis

Labeled by some as the "Father of Psychoanalysis," Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) laid the groundwork for many forms of mental health therapies with his introduction of psychoanalysis and the psychoanalytic or psychodynamic paradigm, which states that psychopathology (the study of the nature and development of mental disorders) is a result of "unconscious conflicts" within a person.

Freud believed that personal development is based on inborn, and particularly sexual, drives that exist in everyone. He also believed that the mind, which he renamed the psyche, is divided into three parts. Functioning together as a whole, these three parts represent specific energies in a person.

THE ID. Present at birth, the id is the part of the mind in charge of all the energy needed to "run" the psyche. It comprises the basic biological urges for food, water, elimination, warmth, affection, and sex. (Originally trained as a neurologist, Freud believed that the source of all of the id's energy is biological.) Later, as a child develops, the energy from the psyche, or the libido, is converted into unconscious psychic energy. The id works on immediate gratification and operates on what Freud called the pleasure principle: A primary process, the id strives to rid the psyche of developing tension by utilizing the pleasure principle, which is the tendency to avoid or reduce pain and obtain pleasure. A classic example describes an infant who, when hungry, works under the pleasure principle to overcome his discomfort when he reaches for his mother's breast.

THE EGO. A primarily conscious part of the psyche, the ego develops during the second half of an infant's first year, and deals with reality and the conscious situations surrounding an individual. Through planning and decision making, which is also called secondary process thinking, the ego learns that operating on the id level is generally not very effective in the long term. The ego, then, operates through realistic thinking, or on the reality principle. The ego gets its energy from the id, which it is also in charge of directing.

THE SUPEREGO. The superego, which develops throughout childhood, operates more or less as a person's conscience. According to Freud, the superego is the part of the mind that houses the rules of the society in which one lives (the conscience), a person's goals, and how one wants to behave (called the ego-ideal). While the id and ego are considered characteristics of the individual, the superego is based more on outside influences, such as family and society. For example, as children grow up, they will learn what actions and behaviors are or are not acceptable; from this new knowledge, they learn how to act to win the praise or affection of a parent.

Freud believed that the superego develops from the ego much as the ego develops from the id. Both the id's instincts and many superego activities are unknown to the mind, while the ego is always conscious of all the psyche's activities. These three parts of the psyche work together in a relationship called psychodynamics.

Psychoanalytic theory and psychoanalysis are based on Freud's second theory of neurotic anxiety, which is the reaction of the ego when a previously repressed id impulse pushes to express itself. The unconscious part of the ego, for example, encounters a situation that reminds it of a repressed childhood conflict, often related to a sexual or aggressive impulse, and is overcome by an overwhelming feeling of tension. Psychoanalytic therapy tries to remove the earlier repression and helps the patient resolve the childhood conflict through the use of adult reality. The childhood repression had prevented the ego from growing; as the conflict is faced and resolved, the ego can reenter a healthy growth pattern.

FREE ASSOCIATION. Raising repressed conflicts occurs through different psychoanalytic techniques, one of which is called free association. In free association, the patient reclines on a couch, facing away from the analyst. The analyst sits near the patient's head and will often take notes during a session. The patient is then free to talk without censoring of any kind. Eventually defenses held by the patient should lessen, and a bond of trust between analyst and patient is established.

DREAM ANALYSIS. Another analytic technique often used in psychoanalysis is dream analysis. This technique follows the Freudian theory that ego defenses are relaxed during sleep, which allows repressed material to enter the sleeper's consciousness. Since these repressed thoughts are so threatening they cannot be experienced in their actual form; the thoughts are disguised in dreams. The dreams, then, become symbolic and significant to the patient's psychoanalytic work.

TRANSFERENCE. Yet another ingredient in psychoanalysis is transference, a patient's response to the analyst which is not in keeping with the analyst-patient relationship but seems, instead, to resemble ways of behaving toward significant people in the patient's past. For example, as a result of feeling neglected as children, patients may feel that they must impress the analyst in order to keep the analyst present. Through observation of these transferred attitudes, the analyst gains insight into the childhood origin of repressed conflicts. The analyst might find that patients who were often home alone as children due to the hardworking but unaware parents could only gain the parental attention they craved when they acted in extreme ways.

One focus of psychoanalysis is the analysis of defenses. This can provide the analyst with a clearer picture of some of the patient's conflict. The therapist studies the patient's defense mechanisms, which are the ego's unconscious

way of warding off a confrontation with anxiety. An example of a defense mechanism would occur when a person who does not want to discuss the death of a close friend or relative during her session might experience a memory lapse when the topic is introduced and she is forced to discuss it. The analyst tries to interpret this patient's behavior, pointing out its defensive nature in order to stimulate the patient to realize that she is avoiding the topic.

Psychoanalytic sessions between patients and their analysts may occur as frequently as five times a week. This frequency is necessary at the beginning of the relationship in order to establish trust between patient and analyst and therefore bring the patient to a level of comfort where repressed conflicts can be uncovered and discussed.

Humanistic and Existential Therapies

Humanistic and existential therapies are therapy techniques that also fall under the category of insight therapies. These therapies are insight-focused, that is, they are based on the assumption that disordered behavior can be overcome by increasing patients' own awareness of their motivations and needs. Whereas psychoanalysis assumes that human nature (the id) is something in need of restraint, humanistic and existential therapists place more emphasis on a person's freedom of choice. Humanistic and existential therapists believe that free will is a person's most valuable trait and is considered a gift to be used wisely. Existential theorists agreed with Freud on some counts, but disagreed on others, which led many to branch out and develop their own therapy techniques.

ANALYTICAL PSYCHOLOGY. Carl Gustav Jung (1887–1961) was one of the theorists who decided to branch out on his own. He defined analytical psychology, which is a mixture of Freudian and humanistic psychology. Jung believed that the role of the unconscious was very important in human behavior. In addition to our unconscious, Jung said there is a collective unconscious as well, which acts as a storage area for all the experiences that all people have had over the centuries; it also, he said, contains positive and creative forces rather than sexual and aggressive ones, as Freud argued. Carl Jung believed that we all have masculine and feminine traits that can be blended within a person; he also thought our spiritual and religious needs are just as important as our libidinal, or physical, sexual needs.

Analytical psychology organizes personality types into groups; the familiar terms "extroverted," or acting out, and "introverted," or turning oneself inward, are Jungian terms used to describe personality traits. Developing a purpose, decision-making, and setting goals are other components of Jung's theory. Whereas Freud believed that a person's current and future behavior is based on experiences of the past, Jungian theorists often focus on dreams, fantasies, and other things that come from or involve the unconscious. Jungian therapy, then, focuses on an analysis of the patient's unconscious processes so the patient can ultimately integrate them into conscious thought and deal with them. Much of the Jungian technique is based on bringing the unconscious into the conscious.

In explaining personality, Jung said there are three levels of consciousness: the conscious, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious.

PSYCHODYNAMIC THERAPY

In 1946, psychodynamic therapy was developed in part through the work of Franz Gabriel Alexander, M.D., and Thomas Morton French, M.D., who were supporters of a briefer analytic therapy than Freud's psychoanalytic theory, using a present and more future-oriented approach. Influenced by such Freudian concepts as the defense mechanism and unconscious motivation, psychodynamic therapy is more active than Freudian therapy and focuses more on present problems and relationships than on childhood conflicts. A briefer, less intensive therapy form, the session frequency and the patient's body position in this therapy matter less than what the patient says and does. With support from the therapist, patients in psychodynamic therapy slowly examine the true sources of their tension and unhappiness by facing repressed feelings and eventually lifting that repression.

The conscious is the only level of which a person is directly aware. This awareness begins right at birth and continues throughout a person's life. At one point, the conscious experiences a stage called individuation, in which the person strives to be different from others and assert himself as an individual. The goal of individuation is to know oneself wholly and completely. This is accomplished, in part, by bringing unconscious material to the conscious.

The personal unconscious is the landing area of the brain for the thoughts, feelings, experiences, and perceptions that are not picked up by the ego. Repressed personal conflicts or unresolved issues are also stored here. Jung wove this concept into his psychoanalytic theory: often thoughts, memories and other material in the personal unconscious are associated with each other and form an involuntary theme. Jung assigned the term "complex" to describe this theme. These complexes can have an extreme emotional effect on a person.

The idea of the collective unconscious is one that separates Jung's theory of psychotherapy from other theories. Jung said the collective unconscious is made up of images and ideas that are independent of the material in one's personal consciousness. Also present in the collective unconscious are instincts, or strong motivations that are present from birth, and archetypes, which are universally known images or symbols that predispose an individual to have a specific feeling or thought about that image. Archetypes will often show themselves in the form of archetypal images, such as the archetype of death or the archetype of the old woman; death's definition is pretty clear (death equals death) and the archetype of the old woman is often used as a representation of wisdom and age.

Jung believed that to fully understand people, one has to appreciate a person's dreams and not just his or her past experiences. Through analytical psychology, the therapist and patient work together to uncover both parts of the person and address conflicts existing in that person.

ADLERIAN PSYCHOLOGY. After a childhood full of traumatic events and serious illness, Alfred Adler (1870–1937) first experienced an interest in psychology while working as a general medical practitioner. After working in this position for a few years, Adler realized he wanted to learn about his patients' social and psychological situations, so he became a psychiatrist (a medical doctor who specializes in the area of the mind). This interest in the whole person was to affect his future work for years to come.

Although at first a member of Freud's psychoanalytic circle, Adler soon branched out on his own and found an interest in the study of the subjectivity of perception as well as the importance of social factors on an individual, as opposed to the importance of biological factors asserted by Freud. Adler's view of personality stressed the importance of the person as a whole but also of the individual's interaction with surrounding society. He also saw the person as a goal-directed, creative individual responsible for his own future.

Because he had been quite ill as a child, Adler had to overcome his own feelings of extreme inferiority (feeling less worthy than others) throughout his childhood. As a result, he emphasized in his own theories of working toward superiority, but not in an antisocial sense. Instead, he viewed people as tied to their surroundings; Adler claimed that a person's fulfillment was based on doing things for the "social good." Like Jung, Adler also argued the importance of working toward personal goals in therapy.

The main factor in Adler's work was a focus on individual psychology, or individual phenomenology—working to help patients get over the "illogical expectations" made on themselves and their lives. He believed that to feel better one must increase one's focus on rational thinking. This belief followed the Jungian theory that the goal of one's life should be individuation, or the conscious realization of one's psychological reality—a reality unlike any other, unique to only that person. As patients become more and more aware of themselves, they combine the unconscious and conscious parts of themselves, thereby becoming stronger and more emotionally whole.

Believing that a person's growth was based on relationships with family during the early years of development, Adler's interest in psychological growth, the prevention of problems, and the improvement of society influenced the creation of child development centers and parent education.

TECHNIQUES AND GOALS OF ADLERIAN THERAPY. Crucial to the Adlerian therapy technique is the establishment of a good therapeutic relationship between therapist and patient, particularly one based on respect and mutual trust. In order for this to happen, therapists and patients must share the same goals for their relationships, which are often uncovered to patients by the therapists. This often includes encouragement by the therapists that the patients can indeed reach their goals through working together with their therapists.

Therapists may also introduce to patients any signs of self-abusive behaviors on the part of the patients, such as resisting or missing therapy sessions. Above all, Adlerian therapists are supportive and empathetic (understanding) to patients; as patients gradually discuss more and more with their therapists, the Adlerians develop knowledge of the lifestyles of their patients. Empathetic responses on the therapists' part often reflect a developed understanding of patients' lifestyles. One of the most important goals of Adlerian therapy is the patient's increase in social interests, as well as an increase in self-awareness and self-confidence.

Adlerian therapy is a practical, humanistic therapy method that helps individuals to identify and change the dysfunction in their lives.

Existential therapy

Another insight therapy, existential therapy is based on the philosophical theory of existentialism, which emphasizes the importance of existence, including one's responsibility for one's own psychological existence. One important component of this theory is dealing with life themes instead of techniques; more than other therapies, existential therapy looks at a patient's self-awareness and his ability to look beyond the immediate problems and events in his or her life and focus instead on problems of human existence.

The first existential therapists were trained in Freud's theories of psychoanalysis, but they disagreed with Freud's stress on the importance of biological drives and unconscious processes in the psyche. Instead, these therapists saw their patients as they were in reality, not as subjects based on theory.

The concepts of existential therapy developed out of the writings of European philosophers, such as Soren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Jaspers, philosopher and theologian Martin Heidegger, and the writer and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre.

TECHNIQUES AND GOALS OF EXISTENTIAL THERAPY. With existential therapy, the focus is not on technique but on existential themes and how they apply to the patient. Through a positive, constructive therapeutic relationship between therapist and patient, existential therapy uncovers common themes occurring in the patient's life. Patients discover that they are not living their lives to the full potential and learn what they must do to realize their full capacity.

The existential therapist must be fully aware of patients and their needs in order to help them attain that position of living to the full of their existence. As patients become more aware of themselves and the results of their actions, they take more responsibility for life and become more "active."

Person-centered Therapy

Once called nondirective therapy, then client-centered therapy, person-centered therapy was developed by American psychologist Carl Rogers. Drawing from years of in-depth clinical research, Rogers's therapy is based on four stages: the developmental stage, the nondirective stage, the client-centered stage, and the person-centered stage.

Person-centered therapy looks at assumptions made about human nature and how people can try to understand these assumptions. Like other humanistic therapists, Rogers believed that people should be responsible for themselves, even when they are troubled. Person-centered therapy takes a positive view of patients, believing that they tend to move toward being fully functioning instead of wallowing in their problems.

TECHNIQUES AND GOALS OF PERSON-CENTERED THERAPY. Person-centered therapy is based more on a way of being rather than a therapy technique. Focusing on understanding and caring instead of diagnosis and advice, Rogers believed that change in the patient could take place if only a few criteria were met: 1. The patient must be anxious or incongruent (lacking harmony) and be in contact with the therapist. 2. The therapist must be genuine; that is, a therapist's words and feelings must agree. 3. The therapist must accept the client and care unconditionally for the client. In addition, the therapist must understand the patient's thoughts and experiences and relay this understanding to the patient.

Rogerian therapists follow the nondirective approach. Although they may want to aid the patient in making decisions that may prove difficult for the patient to realize alone, the therapist cannot provide the answers because a patient must come to conclusions alone. The therapist does not ask questions in a person-centered therapy session, as they may hamper the patient's personal growth, the goal of this therapy.

If the patient is able to perceive these conditions offered by the therapist, then the therapeutic change in the patient will take place and personal growth and higher consciousness can be reached.

Gestalt Therapy

Gestalt psychology rose from the work of Frederich S. Perls, who felt that a focus on perception, and on the development of the whole individual, were important. This was attained by increasing the patient's awareness of unacknowledged feelings and becoming aware of parts of the patient's personality that had been previously denied.

Gestalt therapy has both humanistic and existential aspects; Perls's contemporaries primarily rejected it because Perls disagreed with some of the basic concepts of psychoanalytic theory, such as the importance of the libido and its various transformations in the development of neurosis (mental disorders). Originally developed in the 1940s, the overall concepts of the Gestalt theory state that people are basically good and that this goodness should be allowed to show itself; also, psychological problems originate in frustrations and denials of this innate goodness.

TECHNIQUES AND GOALS OF GESTALT THERAPY. Gestalt therapists focus on the creative aspects of people, instead of their problematic parts. There is a focus on the patient in the therapy room, in the present, instead of a launching into the past; what is most important for the patient is what is happening in that room at that time. If the past enters a session and creates problems for the Gestalt patient, it is brought into the present and discussed. The question of "why" is discouraged in Gestalt therapy, because trying to find causes in the past is considered an attempt to escape the responsibility for decisions made in the present. The therapist plays a role, too: Patients are sometimes coerced (forced) or even bullied into an awareness of every minute detail of the present situation.

Perls believed that awareness acted as a curative, so it is an integral part of this therapy process. He created quite a few techniques for patients, but one well-known practice is the empty chair technique, where a patient projects and then faces those projections. When a patient projects, the ego rejects characteristics or thoughts that are unacceptable or difficult to focus on consciously. For example, a patient may have unresolved feelings about a parent's early death. The patient in Gestalt therapy will sit facing an empty chair and pretend that he is facing the dead parent. The patient can then consciously face, and eventually overcome, the unresolved feelings or conflicts toward that parent.

The goal of Gestalt therapy is to help patients understand and accept their needs and fears as well as increase awareness of how they keep themselves from reaching their goals and taking care of their needs. Also, the Gestalt therapist strives to help the patient encounter the world in a nonjudgmental way. Concentration on the "here and now" and on the patient as responsible for his or her actions and behavior is an end result.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: